From a childhood in the cancer ward to a lifetime in Alabama’s coverage gap

By Whit Sides, Cover Alabama storyteller, Alabama Arise

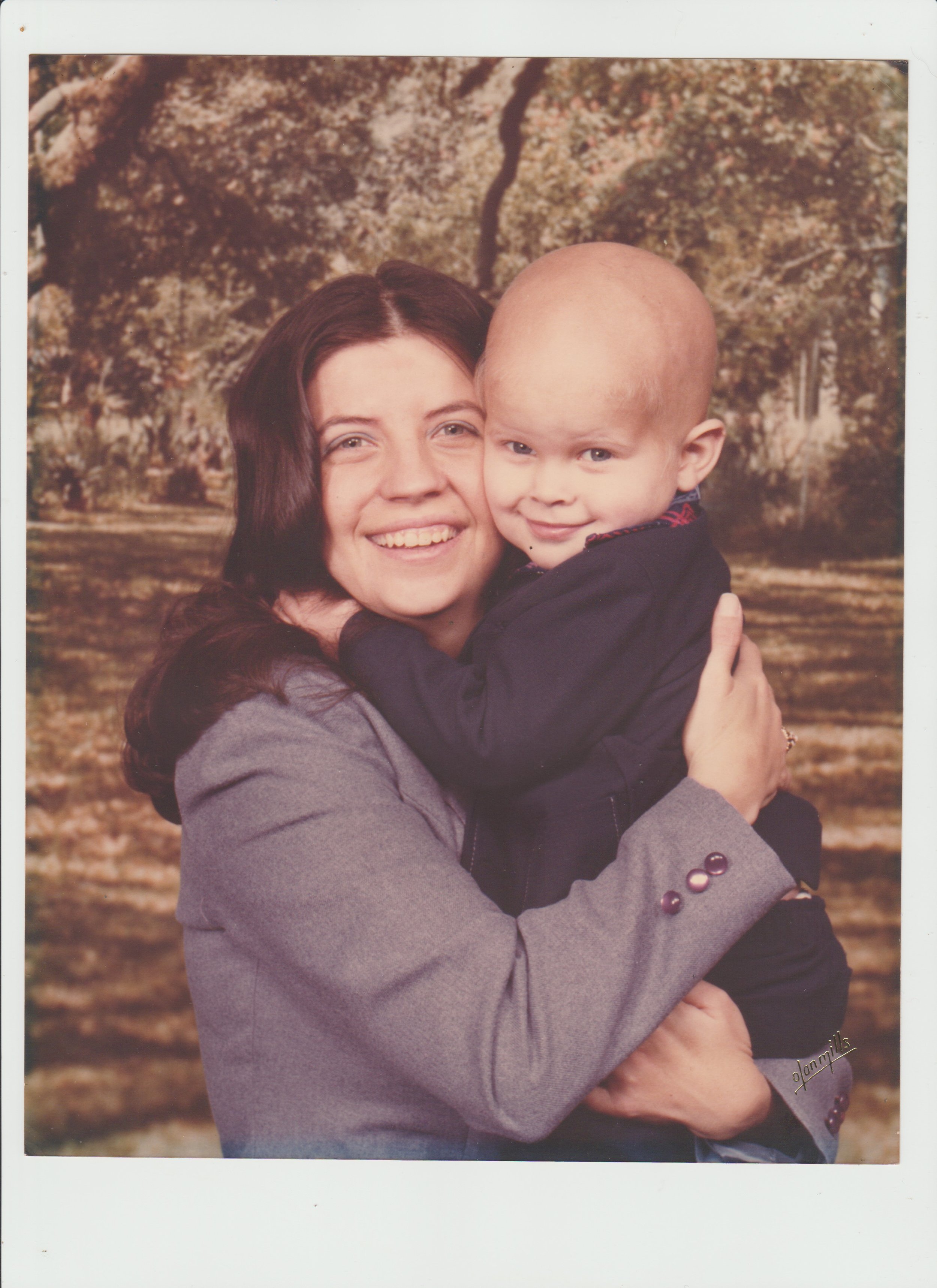

Lary Brooks of New Hope, Ala., has dealt with health issues stemming from childhood cancer for his entire life. (Photo courtesy of Lary Brooks)

Lary Brooks is a fighter.

At just 2 1/2 years old, he was diagnosed with acute lymphocytic leukemia, a bone and blood cancer that nearly took his life. Lary survived thanks to the life-saving treatment he received at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn.

“I was a week from dying when they found it,” Lary recalled about his childhood cancer diagnosis. “From 1979 to 1982, I was under treatment — 1,800 units of chemo and radiation.”

Those intense treatments took a severe toll on his body that affected nearly every aspect of his life, even as an adult.

“I’ve had my L4, L5 vertebrae blown out because of so many spinal taps,” he said. Doctors used the painful procedure to monitor his progress throughout childhood.

Lary’s courage in the face of pain earned him the name “OK Kid.” When the doctors at St. Jude asked him how he felt during these intense procedures, he always responded, “I’m OK.”

But from the time he was young, Lary said, he felt like he hadn’t been able to live life to its fullest.

“At one time, I had my left arm in a full cast and my right arm in a half cast,” he said. “I stepped into a hole while playing with my sister and ended up breaking my wrist.”

Today, at age 47, Lary lives with his family in New Hope, a small town southeast of Huntsville. He suffers from osteopenia and scoliosis. The lingering effects of his childhood cancer caused a loss of spine density and chronic pain that often leaves him unable to work.

‘I’m ready to go back to work now’

Over the years, Lary has found jobs in construction, as a waiter and as an automotive tech. But each job ended when he was injured or needed care.

Most recently, Lary suffered a fall that required major facial surgery to reconstruct his jaw. The surgery left him with more medical debt and yet another battle to get the care he desperately needed.

Originally, doctors told him he’d be recovering for six to eight weeks. But now it’s looking more like Lary won’t be able to work for six months.

“I’m ready to go back to work now, but I’ve got to get released from the doctors,” Lary said, anxious to return to his life.

Yet with no health insurance, he can only access emergency care. That means he can’t see the specialists he needs to manage his everyday issues — or the crippling pain that comes from them.

Without access to the prescriptions he needs, Lary is left with few pain management options. They provide little to no relief.

“I don’t have insurance, so I can’t treat my problems as they come up, and everything just deteriorates,” he said. “The only thing I’m able to do … is over-the-counter pain medication, but it doesn’t work.”

Alabama’s failure to expand Medicaid to cover adults with low incomes has left nearly 200,000 residents like Lary in the health coverage gap, unable to afford private insurance but not eligible for Medicaid. Our state is one of only 10 yet to accept federal funds that would offer coverage to folks like Lary.

Without Medicaid expansion, Lary must either rely on expensive emergency room visits for temporary relief or continue to endure debilitating pain every day. As he recovers at home from his most recent surgery, he’s left with few options.

A life in pain

“I walk around with a pain level of 10, 24/7, seven days a week,” Lary said. “The only thing I can think about or stay focused on is my body pain because it’s like my brain will not allow me to focus on anything else.”

Lary said his pain is compounded by the limitations placed on health care providers due to the opioid crisis.

“I ask the doctors if there’s any way that I can get help to where I can still stay at work on a full-time basis,” he said. “But with the opiate crisis, they won’t prescribe chronic pain medication without me being established in a pain clinic. So I’m reduced to going down to part-time at work but struggling with my pain all the time.”

Lary’s mother, Brenda Brooks, said finding payment assistance through local hospitals for Lary’s care has become a part-time job itself. She often digs through past tax returns, prints out the past few months of bank statements and tracks down medical records from different doctors.

Brenda said that even with his extensive medical history, Lary has been denied for disability benefits many times. And it hasn’t been for a lack of his mother trying.

“Last time, the disability doctor told us Lary is able to work, as something like a truck driver? He’s not supposed to lift over 25 pounds. Tell me how that works,” Brenda asked.

Brenda Brooks holds her son Lary in spring 1980. The picture was taken about six months after Lary was diagnosed with leukemia. (Photo courtesy of Brenda Brooks)

‘I just wait until I can’t stand it anymore’

So for now, Lary keeps trying to find work while not being able to afford coverage or consistent care. He said he manages by spacing out care, or sometimes avoiding it altogether.

“It’s mainly just choosing the right time to go to the doctor,” he said. “I mean, with my pain and everything, and me being a diabetic, I’m usually having to wait probably six months in order to go.”

Ideally, Lary should be able to go to the doctor monthly. But living in the coverage gap forces him to make tough decisions about whether to seek care when he needs it.

“I spread it out and then choose what pain level I’m in before I either go to the ER or I just wait until I can’t stand it anymore,” Lary said.

It’s a piecemeal plan for pain management caused by living in the coverage gap. When things do become unbearable, his mother said, it’s never without a cost.

“We still owe UAB Hospital for surgery, like $11,000,” Brenda said. “That’s not including the doctor visits. That’s just the surgery and the hospital time.”

On top of that, Lary said his debt at Huntsville Hospital, the closest to his home, is nearly $30,000.

A mother turned warrior

Lary said his mother has been his greatest advocate. A substitute teacher, she has taken up the fight to get her son the care he needs.

“I’ve called everyone — local lawmakers, even Gov. Kay Ivey,” Brenda said. “I’ll do whatever it takes to get him the care he deserves.”

Finally, she reached out to Cover Alabama to share her family’s story.

“I want everyone to understand that people in the gap like Lary just need fair coverage. They aren’t looking for a handout. He pays taxes, so I don’t think it should even be looked at that way,” Brenda said.

Lary and Brenda Brooks pose inside their home in New Hope, Ala., in October 2024. (Photo by Whit Sides)

Medicaid expansion could help Lary access the specialists he needs without relying on the emergency room for short-term fixes.

“If I could get in to see a good doctor and stay with them, I’d be able to live a normal life,” he said.

For now, Lary’s lack of health coverage affects his freedom and autonomy as an adult, including his relationships.

For Lary, the effects of living without insurance extend beyond his physical health. He recently had to ask his uncle for $3,000 to pay for treatment. He said it was a tough blow mentally.

And romantically, he finds it difficult to find partners or companionship because he feels like “there’s always a catch.”

“I’ve met lots of women, but when I told them exactly what my story was, most of them decided to walk out because they thought it was too much trouble,” he said. “That’s why I’m 47 and still single.”

Hope for a better Alabama

Lary remains hopeful and tries to keep a positive outlook. But he said it’s important to be honest about the isolation he goes through daily.

“It messes with your confidence a little bit,” he said. “I want to be a productive member of society. I don’t want to feel like a burden.”

Medicaid expansion would help Lary live a more fulfilling life, free from the constant worry of mounting medical debt and inadequate care. It would give him and thousands of other Alabamians the chance to work rather than being sidelined by a lack of support.

“You’ve got all these people in this state alone living in the gap,” Lary said. “Imagine how many more in other states like Texas. If we can’t work, our state doesn’t get the tax money.”

For Lary, this is more than a political issue — it’s a matter of survival. As he continues to fight for his health, he holds on to the hope that the system will change one day. In the meantime, Brenda will keep advocating for her son, hoping her calls to lawmakers won’t fall on deaf ears.

“I’ve sent out so many emails and only ever got one response,” Brenda said. “They are supposed to represent people in their area, especially those who need the help. And they’re supposed to push to get what their constituents need, like expanding Medicaid.”

Lary and Brenda Brooks embrace inside their home in New Hope, Ala., in October 2024. (Photo by Whit Sides)

‘The honest way’

Lary said caring for him as a child and not being able to “fix it” was a traumatic experience for his family. He said that’s his constant motivation now: wanting to fix anything he can for others.

Even while recovering from surgery, Lary still finds time to help others. He’s a member of St. Jude’s alumni program, which allows cancer survivors like him to work with doctors to develop new treatments for kids living with bone cancers similar to the one he fought.

“I’m trying to do things the honest way,” Lary said. “I just wish there were systems to help me keep doing that.”

About Alabama Arise and Cover Alabama

Whit Sides is the Cover Alabama storyteller for Alabama Arise, a statewide, member-led organization advancing public policies to improve the lives of Alabamians who are marginalized by poverty. Arise’s membership includes faith-based, community, nonprofit and civic groups, grassroots leaders and individuals from across Alabama. Email: whit@alarise.org.

Arise is a founding member of the Cover Alabama coalition. Cover Alabama is a nonpartisan alliance of advocacy groups, businesses, community organizations, consumer groups, health care providers and religious congregations advocating for Alabama to provide quality, affordable health coverage to its residents and implement a sustainable health care system.

Stories help to put a human face on the health care policy issues. By sharing your story, you help speak for people who may be facing issues just like yours.